tutorials.md 50 KB

Timescaledb - Tutorials

Pages: 12

Advanced data management

URL: llms-txt#advanced-data-management

Contents:

- Hypertable chunk time intervals and automation policies

- Automatically delete older tick data

- Automatically delete older candlestick data

- Automatically compress tick data

- Automatically compress candlestick data

The final part of this tutorial shows you some more advanced techniques to efficiently manage your tick and candlestick data long-term. TimescaleDB is equipped with multiple features that help you manage your data lifecycle and reduce your disk storage needs as your data grows.

This section contains four examples of how you can set up automation policies on your tick data hypertable and your candlestick continuous aggregates. This can help you save on disk storage and improve the performance of long-range analytical queries by automatically:

- Deleting older tick data

- Deleting older candlestick data

- Compressing tick data

- Compressing candlestick data

Before you implement any of these automation policies, it's important to have a high-level understanding of chunk time intervals in TimescaleDB hypertables and continuous aggregates. The chunk time interval you set for your tick data table directly affects how these automation policies work. For more information, see the [hypertables and chunks][chunks] section.

Hypertable chunk time intervals and automation policies

TimescaleDB uses hypertables to provide a high-level and familiar abstraction layer to interact with Postgres tables. You just need to access one hypertable to access all of your time-series data.

Under the hood, TimescaleDB creates chunks based on the timestamp column.

Each chunk size is determined by the [chunk_time_interval][interval]

parameter. You can provide this parameter when creating the hypertable, or you can change

it afterwards. If you don't provide this optional parameter, the

chunk time interval defaults to 7 days. This means that each of the

chunks in the hypertable contains 7 days' worth of data.

Knowing your chunk time interval is important. All of the TimescaleDB automation policies described in this section depend on this information, and the chunk time interval fundamentally affects how these policies impact your data.

In this section, learn about these automation policies and how they work in the context of financial tick data.

Automatically delete older tick data

Usually, the older your time-series data, the less relevant and useful it is. This is often the case with tick data as well. As time passes, you might not need the raw tick data any more, because you only want to query the candlestick aggregations. In this scenario, you can decide to remove tick data automatically from your hypertable after it gets older than a certain time interval.

TimescaleDB has a built-in way to automatically remove raw data after a specific time. You can set up this automation using a [data retention policy][retention]:

When you run this, it adds a data retention policy to the crypto_ticks

hypertable that removes a chunk after all the data in the chunk becomes

older than 7 days. All records in the chunk need to be

older than 7 days before the chunk is dropped.

Knowledge of your hypertable's chunk time interval

is crucial here. If you were to set a data retention policy with

INTERVAL '3 days', the policy would not remove any data after three days, because your chunk time interval is seven days. Even after three

days have passed, the most recent chunk still contains data that is newer than three

days, and so cannot be removed by the data retention policy.

If you want to change this behavior, and drop chunks more often and sooner, experiment with different chunk time intervals. For example, if you set the chunk time interval to be two days only, you could create a retention policy with a 2-day interval that would drop a chunk every other day (assuming you're ingesting data in the meantime).

For more information, see the [data retention][retention] section.

Make sure none of the continuous aggregate policies intersect with a data retention policy. It's possible to keep the candlestick data in the continuous aggregate and drop tick data from the underlying hypertable, but only if you materialize data in the continuous aggregate first, before the data is dropped from the underlying hypertable.

Automatically delete older candlestick data

Deleting older raw tick data from your hypertable while retaining aggregate views for longer periods is a common way of minimizing disk utilization. However, deleting older candlestick data from the continuous aggregates can provide another method for further control over long-term disk use. TimescaleDB allows you to create data retention policies on continuous aggregates as well.

Continuous aggregates also have chunk time intervals because they use hypertables in the background. By default, the continuous aggregate's chunk time interval is 10 times what the original hypertable's chunk time interval is. For example, if the original hypertable's chunk time interval is 7 days, the continuous aggregates that are on top of it will have a 70 day chunk time interval.

You can set up a data retention policy to remove old data from

your one_min_candle continuous aggregate:

This data retention policy removes chunks from the continuous aggregate

that are older than 70 days. In TimescaleDB, this is determined by the

range_end property of a hypertable, or in the case of a continuous

aggregate, the materialized hypertable. In practice, this means that if

you were to

define a data retention policy of 30 days for a continuous aggregate that has

a chunk_time_interval of 70 days, data would not be removed from the

continuous aggregates until the range_end of a chunk is at least 70

days older than the current time, due to the chunk time interval of the

original hypertable.

Automatically compress tick data

TimescaleDB allows you to keep your tick data in the hypertable but still save on storage costs with TimescaleDB's native compression. You need to enable compression on the hypertable and set up a compression policy to automatically compress old data.

Enable compression on crypto_ticks hypertable:

Set up compression policy to compress data that's older than 7 days:

Executing these two SQL scripts compresses chunks that are older than 7 days.

For more information, see the [compression][compression] section.

Automatically compress candlestick data

Beginning with [TimescaleDB 2.6][release-blog], you can also set up a compression policy on your continuous aggregates. This is a useful feature if you store a lot of historical candlestick data that consumes significant disk space, but you still want to retain it for longer periods.

Enable compression on the one_min_candle view:

Add a compression policy to compress data after 70 days:

Before setting a compression policy on any of the candlestick views, set a refresh policy first. The compression policy interval should be set so that actively refreshed time intervals are not compressed.

[Read more about compressing continuous aggregates.][caggs-compress]

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/energy-data/dataset-energy/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

SELECT add_retention_policy('crypto_ticks', INTERVAL '7 days');

Example 2 (sql):

SELECT add_retention_policy('one_min_candle', INTERVAL '70 days');

Example 3 (sql):

ALTER TABLE crypto_ticks SET (

timescaledb.compress,

timescaledb.compress_segmentby = 'symbol'

);

Example 4 (sql):

SELECT add_compression_policy('crypto_ticks', INTERVAL '7 days');

Tutorials

URL: llms-txt#tutorials

Tiger Data tutorials are designed to help you get up and running with Tiger Data products. They walk you through a variety of scenarios using example datasets, to teach you how to construct interesting queries, find out what information your database has hidden in it, and even give you options for visualizing and graphing your results.

- Real-time analytics

- [Analytics on energy consumption][rta-energy]: make data-driven decisions using energy consumption data.

- [Analytics on transport and geospatial data][rta-transport]: optimize profits using geospatial transport data.

- Cryptocurrency

- [Query the Bitcoin blockchain][beginner-crypto]: do your own research on the Bitcoin blockchain.

- [Analyze the Bitcoin blockchain][intermediate-crypto]: discover the relationship between transactions, blocks, fees, and miner revenue.

- Finance

- [Analyze financial tick data][beginner-finance]: chart the trading highs and lows for your favorite stock.

- [Ingest real-time financial data using WebSocket][advanced-finance]: use a websocket connection to visualize the trading highs and lows for your favorite stock.

- IoT

- [Simulate an IoT sensor dataset][iot]: simulate an IoT sensor dataset and run simple queries on it.

- Cookbooks

- [Tiger community cookbook][cookbooks]: get suggestions from the Tiger community about how to resolve common issues.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/_troubleshooting/compression-dml-tuple-limit/ =====

Query time-series data tutorial - set up dataset

URL: llms-txt#query-time-series-data-tutorial---set-up-dataset

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Optimize time-series data in hypertables

- Create standard Postgres tables for relational data

- Load trip data

This tutorial uses a dataset that contains historical data from the New York City Taxi and Limousine

Commission [NYC TLC][nyc-tlc], in a hypertable named rides. It also includes a separate

tables of payment types and rates, in a regular Postgres table named

payment_types, and rates.

To follow the steps on this page:

- Create a target [Tiger Cloud service][create-service] with the Real-time analytics capability.

You need [your connection details][connection-info]. This procedure also works for [self-hosted TimescaleDB][enable-timescaledb].

Optimize time-series data in hypertables

Time-series data represents how a system, process, or behavior changes over time. [Hypertables][hypertables-section] are Postgres tables that help you improve insert and query performance by automatically partitioning your data by time. Each hypertable is made up of child tables called chunks. Each chunk is assigned a range of time, and only contains data from that range.

Hypertables exist alongside regular Postgres tables. You interact with hypertables and regular Postgres tables in the same way. You use regular Postgres tables for relational data.

- Create a hypertable to store the taxi trip data

If you are self-hosting TimescaleDB v2.19.3 and below, create a [Postgres relational table][pg-create-table], then convert it using [create_hypertable][create_hypertable]. You then enable hypercore with a call to [ALTER TABLE][alter_table_hypercore].

Add another dimension to partition your hypertable more efficiently

Create an index to support efficient queries

Index by vendor, rate code, and passenger count:

Create standard Postgres tables for relational data

When you have other relational data that enhances your time-series data, you can

create standard Postgres tables just as you would normally. For this dataset,

there are two other tables of data, called payment_types and rates.

Add a relational table to store the payment types data

Add a relational table to store the rates data

You can confirm that the scripts were successful by running the \dt command in

the psql command line. You should see this:

When you have your database set up, you can load the taxi trip data into the

rides hypertable.

This is a large dataset, so it might take a long time, depending on your network connection.

- Download the dataset:

Use your file manager to decompress the downloaded dataset, and take a note of the path to the

nyc_data_rides.csvfile.At the psql prompt, copy the data from the

nyc_data_rides.csvfile into your hypertable. Make sure you point to the correct path, if it is not in your current working directory:

You can check that the data has been copied successfully with this command:

You should get five records that look like this:

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/nyc-taxi-cab/index/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

CREATE TABLE "rides"(

vendor_id TEXT,

pickup_datetime TIMESTAMP WITHOUT TIME ZONE NOT NULL,

dropoff_datetime TIMESTAMP WITHOUT TIME ZONE NOT NULL,

passenger_count NUMERIC,

trip_distance NUMERIC,

pickup_longitude NUMERIC,

pickup_latitude NUMERIC,

rate_code INTEGER,

dropoff_longitude NUMERIC,

dropoff_latitude NUMERIC,

payment_type INTEGER,

fare_amount NUMERIC,

extra NUMERIC,

mta_tax NUMERIC,

tip_amount NUMERIC,

tolls_amount NUMERIC,

improvement_surcharge NUMERIC,

total_amount NUMERIC

) WITH (

tsdb.hypertable,

tsdb.partition_column='pickup_datetime',

tsdb.create_default_indexes=false

);

Example 2 (sql):

SELECT add_dimension('rides', by_hash('payment_type', 2));

Example 3 (sql):

CREATE INDEX ON rides (vendor_id, pickup_datetime DESC);

CREATE INDEX ON rides (rate_code, pickup_datetime DESC);

CREATE INDEX ON rides (passenger_count, pickup_datetime DESC);

Example 4 (sql):

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "payment_types"(

payment_type INTEGER,

description TEXT

);

INSERT INTO payment_types(payment_type, description) VALUES

(1, 'credit card'),

(2, 'cash'),

(3, 'no charge'),

(4, 'dispute'),

(5, 'unknown'),

(6, 'voided trip');

Plot geospatial time-series data tutorial

URL: llms-txt#plot-geospatial-time-series-data-tutorial

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Steps in this tutorial

- About querying data with Timescale

New York City is home to about 9 million people. This tutorial uses historical data from New York's yellow taxi network, provided by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission [NYC TLC][nyc-tlc]. The NYC TLC tracks over 200,000 vehicles making about 1 million trips each day. Because nearly all of this data is time-series data, proper analysis requires a purpose-built time-series database, like Timescale.

In the [beginner NYC taxis tutorial][beginner-fleet], you looked at constructing queries that looked at how many rides were taken, and when. The NYC taxi cab dataset also contains information about where each ride was picked up. This is geospatial data, and you can use a Postgres extension called PostGIS to examine where rides are originating from. Additionally, you can visualize the data in Grafana, by overlaying it on a map.

Before you begin, make sure you have:

- Signed up for a [free Tiger Data account][cloud-install].

- [](#) If you want to graph your queries, signed up for a [Grafana account][grafana-setup].

Steps in this tutorial

This tutorial covers:

- [Setting up your dataset][dataset-nyc]: Set up and connect to a Timescale

service, and load data into your database using

psql. - [Querying your dataset][query-nyc]: Analyze a dataset containing NYC taxi trip data using Tiger Cloud and Postgres, and plot the results in Grafana.

About querying data with Timescale

This tutorial uses the [NYC taxi data][nyc-tlc] to show you how to construct queries for geospatial time-series data. The analysis you do in this tutorial is similar to the kind of analysis civic organizations do to plan new roads and public services.

It starts by teaching you how to set up and connect to a Tiger Cloud service,

create tables, and load data into the tables using psql. If you have already

completed the [first NYC taxis tutorial][beginner-fleet], then you already

have the dataset loaded, and you can skip [straight to the queries][plot-nyc].

You then learn how to conduct analysis and monitoring on your dataset. It walks you through using Postgres queries with the PostGIS extension to obtain information, and plotting the results in Grafana.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/nyc-taxi-geospatial/plot-nyc/ =====

Query candlestick views

URL: llms-txt#query-candlestick-views

Contents:

- 1-min BTC/USD candlestick chart

- 1-hour BTC/USD candlestick chart

- 1-day BTC/USD candlestick chart

- BTC vs. ETH 1-day price changes delta line chart

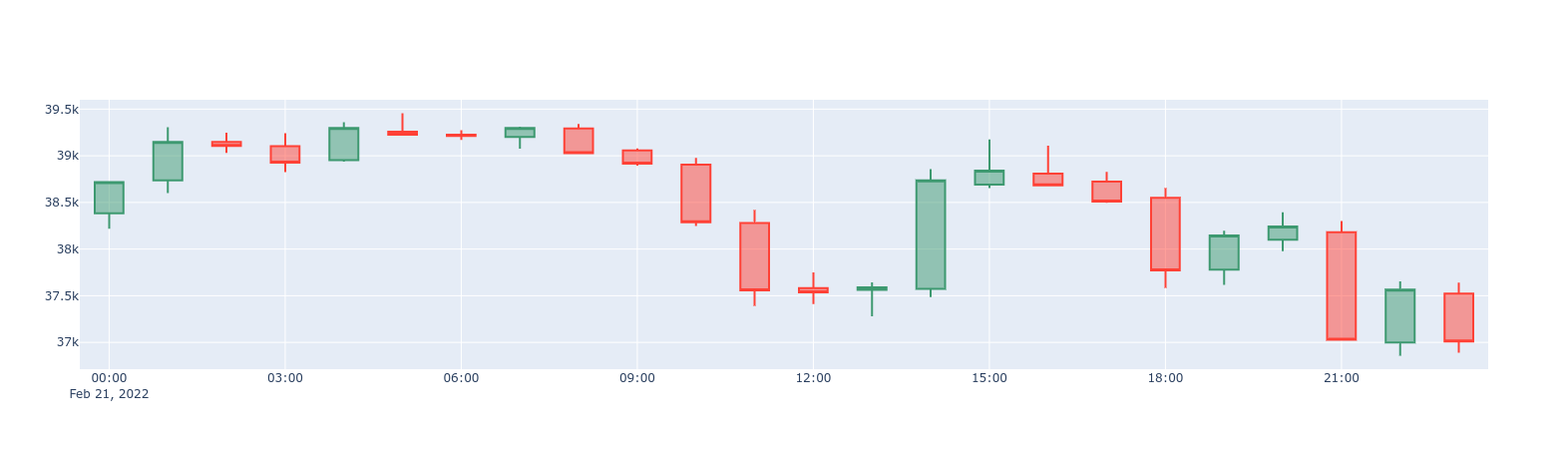

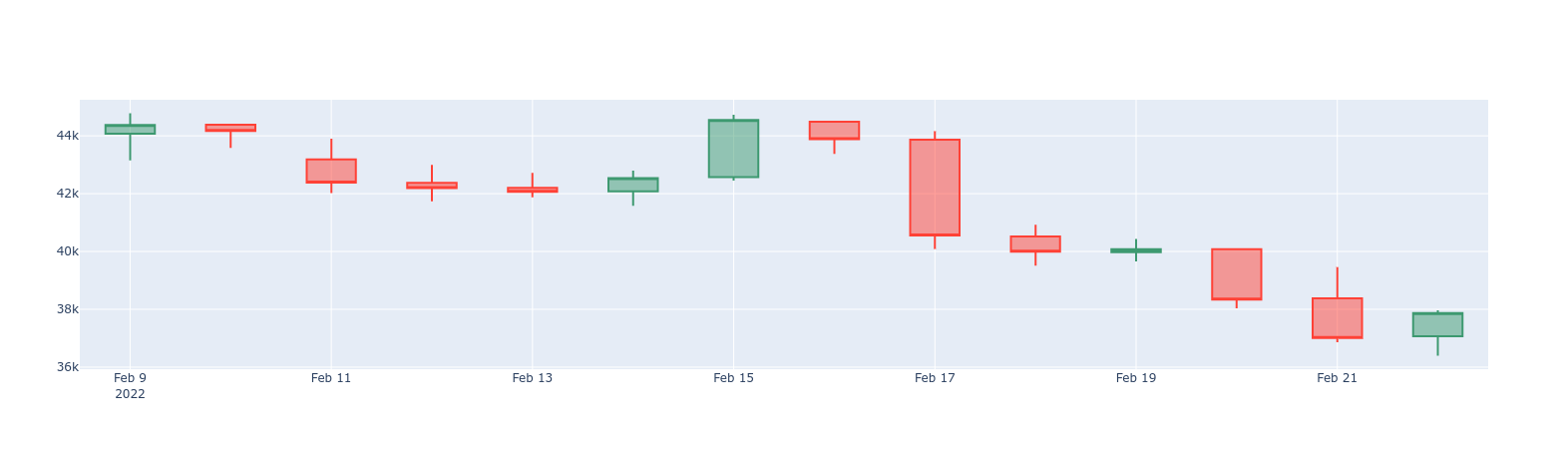

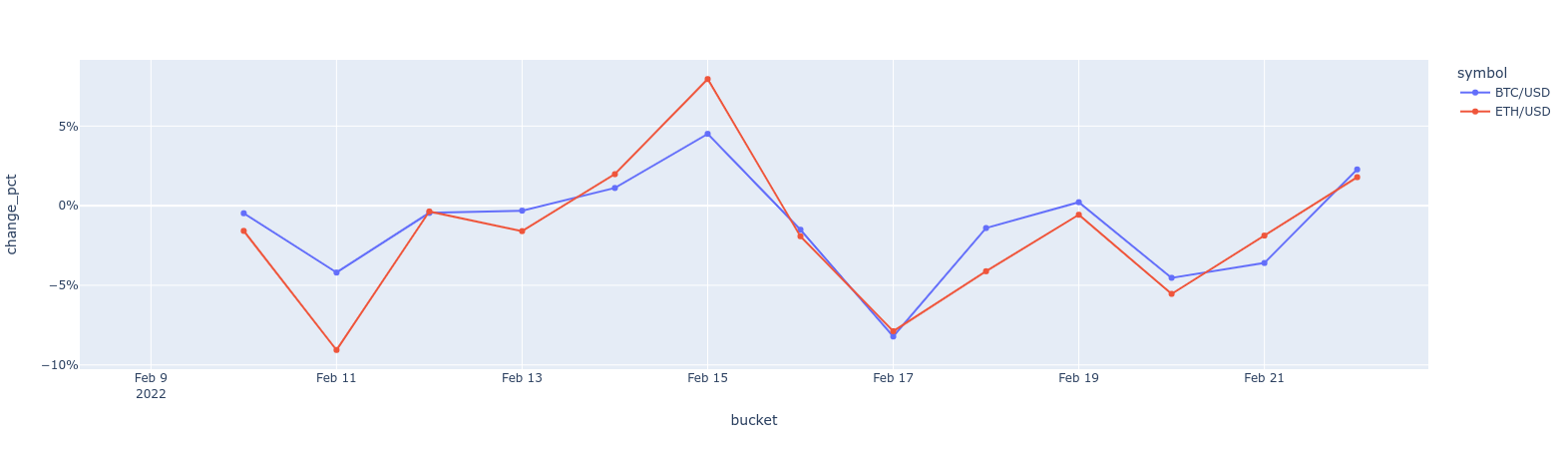

So far in this tutorial, you have created the schema to store tick data, and set up multiple candlestick views. In this section, use some example candlestick queries and see how they can be represented in data visualizations.

The queries in this section are example queries. The sample data

provided with this tutorial is updated on a regular basis to have near-time

data, typically no more than a few days old. Our sample queries reflect time

filters that might be longer than you would normally use, so feel free to

modify the time filter in the WHERE clause as the data ages, or as you begin

to insert updated tick readings.

1-min BTC/USD candlestick chart

Start with a one_min_candle continuous aggregate, which contains

1-min candlesticks:

1-hour BTC/USD candlestick chart

If you find that 1-min candlesticks are too granular, you can query the

one_hour_candle continuous aggregate containing 1-hour candlesticks:

1-day BTC/USD candlestick chart

To zoom out even more, query the one_day_candle

continuous aggregate, which has one-day candlesticks:

BTC vs. ETH 1-day price changes delta line chart

You can calculate and visualize the price change differences between

two symbols. In a previous example, you saw how to do this by comparing the

opening and closing prices. But what if you want to compare today's closing

price with yesterday's closing price? Here's an example how you can achieve

this by using the [LAG()][lag] window function on an already existing

candlestick view:

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/OLD-financial-candlestick-tick-data/design-tick-schema/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

SELECT * FROM one_min_candle

WHERE symbol = 'BTC/USD' AND bucket >= NOW() - INTERVAL '24 hour'

ORDER BY bucket

Example 2 (sql):

SELECT * FROM one_hour_candle

WHERE symbol = 'BTC/USD' AND bucket >= NOW() - INTERVAL '2 day'

ORDER BY bucket

Example 3 (sql):

SELECT * FROM one_day_candle

WHERE symbol = 'BTC/USD' AND bucket >= NOW() - INTERVAL '14 days'

ORDER BY bucket

Example 4 (sql):

SELECT *, ("close" - LAG("close", 1) OVER (PARTITION BY symbol ORDER BY bucket)) / "close" AS change_pct

FROM one_day_candle

WHERE symbol IN ('BTC/USD', 'ETH/USD') AND bucket >= NOW() - INTERVAL '14 days'

ORDER BY bucket

Query time-series data tutorial

URL: llms-txt#query-time-series-data-tutorial

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Steps in this tutorial

- About querying data with Timescale

New York City is home to about 9 million people. This tutorial uses historical data from New York's yellow taxi network, provided by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission [NYC TLC][nyc-tlc]. The NYC TLC tracks over 200,000 vehicles making about 1 million trips each day. Because nearly all of this data is time-series data, proper analysis requires a purpose-built time-series database, like Timescale.

Before you begin, make sure you have:

- Signed up for a [free Tiger Data account][cloud-install].

Steps in this tutorial

This tutorial covers:

- [Setting up your dataset][dataset-nyc]: Set up and connect to a Timescale

service, and load data into your database using

psql. - [Querying your dataset][query-nyc]: Analyze a dataset containing NYC taxi trip data using Tiger Cloud and Postgres.

- [Bonus: Store data efficiently][compress-nyc]: Learn how to store and query your NYC taxi trip data more efficiently using compression feature of Timescale.

About querying data with Timescale

This tutorial uses the [NYC taxi data][nyc-tlc] to show you how to construct queries for time-series data. The analysis you do in this tutorial is similar to the kind of analysis data science organizations use to do things like plan upgrades, set budgets, and allocate resources.

It starts by teaching you how to set up and connect to a Tiger Cloud service,

create tables, and load data into the tables using psql.

You then learn how to conduct analysis and monitoring on your dataset. It walks you through using Postgres queries to obtain information, including how to use JOINs to combine your time-series data with relational or business data.

If you have been provided with a pre-loaded dataset on your Tiger Cloud service, go directly to the queries section.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/nyc-taxi-cab/query-nyc/ =====

Energy consumption data tutorial - query the data

URL: llms-txt#energy-consumption-data-tutorial---query-the-data

Contents:

- What is the energy consumption by the hour of the day?

- Finding how many kilowatts of energy is consumed on an hourly basis

- What is the energy consumption by the day of the week?

- Finding energy consumption during the weekdays

- What is the energy consumption on a monthly basis?

- Finding energy consumption for each month of the year

When you have your dataset loaded, you can start constructing some queries to discover what your data tells you. This tutorial uses [TimescaleDB hyperfunctions][about-hyperfunctions] to construct queries that are not possible in standard Postgres.

In this section, you learn how to construct queries, to answer these questions:

What is the energy consumption by the hour of the day?

When you have your database set up for energy consumption data, you can construct a query to find the median and the maximum consumption of energy on an hourly basis in a typical day.

Finding how many kilowatts of energy is consumed on an hourly basis

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the energy consumption dataset.

At the psql prompt, use the TimescaleDB Toolkit functionality to get calculate the fiftieth percentile or the median. Then calculate the maximum energy consumed using the standard Postgres max function:

The data you get back looks a bit like this:

What is the energy consumption by the day of the week?

You can also check how energy consumption varies between weekends and weekdays.

Finding energy consumption during the weekdays

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the energy consumption dataset.

At the psql prompt, use this query to find difference in consumption during the weekdays and the weekends:

The data you get back looks a bit like this:

What is the energy consumption on a monthly basis?

You may also want to check the energy consumption that occurs on a monthly basis.

Finding energy consumption for each month of the year

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the energy consumption dataset.

At the psql prompt, use this query to find consumption for each month of the year:

The data you get back looks a bit like this:

[](#) To visualize this in Grafana, create a new panel, and select the

Bar Chartvisualization. Select the energy consumption dataset as your data source, and type the query from the previous step. In theFormat assection, selectTable.[](#) Select a color scheme so that different consumptions are shown in different colors. In the options panel, under

Standard options, change theColor schemeto a usefulby valuerange.

<img

class="main-content__illustration"

src="https://assets.timescale.com/docs/images/grafana-energy.webp"

width={1375} height={944}

alt="Visualizing energy consumptions in Grafana"

/>

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/energy-data/index/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

WITH per_hour AS (

SELECT

time,

value

FROM kwh_hour_by_hour

WHERE "time" at time zone 'Europe/Berlin' > date_trunc('month', time) - interval '1 year'

ORDER BY 1

), hourly AS (

SELECT

extract(HOUR FROM time) * interval '1 hour' as hour,

value

FROM per_hour

)

SELECT

hour,

approx_percentile(0.50, percentile_agg(value)) as median,

max(value) as maximum

FROM hourly

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1;

Example 2 (sql):

hour | median | maximum

----------+--------------------+---------

00:00:00 | 0.5998949812512439 | 0.6

01:00:00 | 0.5998949812512439 | 0.6

02:00:00 | 0.5998949812512439 | 0.6

03:00:00 | 1.6015944383271534 | 1.9

04:00:00 | 2.5986701108275327 | 2.7

05:00:00 | 1.4007385207185301 | 3.4

06:00:00 | 0.5998949812512439 | 2.7

07:00:00 | 0.6997720645753496 | 0.8

08:00:00 | 0.6997720645753496 | 0.8

09:00:00 | 0.6997720645753496 | 0.8

10:00:00 | 0.9003240409125329 | 1.1

11:00:00 | 0.8001143897618259 | 0.9

Example 3 (sql):

WITH per_day AS (

SELECT

time,

value

FROM kwh_day_by_day

WHERE "time" at time zone 'Europe/Berlin' > date_trunc('month', time) - interval '1 year'

ORDER BY 1

), daily AS (

SELECT

to_char(time, 'Dy') as day,

value

FROM per_day

), percentile AS (

SELECT

day,

approx_percentile(0.50, percentile_agg(value)) as value

FROM daily

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1

)

SELECT

d.day,

d.ordinal,

pd.value

FROM unnest(array['Sun', 'Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat']) WITH ORDINALITY AS d(day, ordinal)

LEFT JOIN percentile pd ON lower(pd.day) = lower(d.day);

Example 4 (sql):

day | ordinal | value

-----+---------+--------------------

Mon | 2 | 23.08078714975423

Sun | 1 | 19.511430831944395

Tue | 3 | 25.003118897837307

Wed | 4 | 8.09300571759772

Sat | 7 |

Fri | 6 |

Thu | 5 |

Query time-series data tutorial - query the data

URL: llms-txt#query-time-series-data-tutorial---query-the-data

Contents:

- How many rides take place every day?

- Finding how many rides take place every day

- What is the average fare amount?

- Finding the average fare amount

- How many rides of each rate type were taken?

- Finding the number of rides for each fare type

- Displaying the number of rides for each fare type

- What kind of trips are going to and from airports

- Finding what kind of trips are going to and from airports

- How many rides took place on New Year's Day 2016?

When you have your dataset loaded, you can start constructing some queries to discover what your data tells you. In this section, you learn how to write queries that answer these questions:

- How many rides take place each day?

- What is the average fare amount?

- How many rides of each rate type were taken?

- What kind of trips are going to and from airports?

- How many rides took place on New Year's Day 2016?

How many rides take place every day?

This dataset contains ride data for January 2016. To find out how many rides

took place each day, you can use a SELECT statement. In this case, you want to

count the total number of rides each day, and show them in a list by date.

Finding how many rides take place every day

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken in the first week of January 2016, and return a count of rides for each day:

The result of the query looks like this:

What is the average fare amount?

You can include a function in your SELECT query to determine the average fare

paid by each passenger.

Finding the average fare amount

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken in the first week of January 2016, and return the average fare paid on each day:

The result of the query looks like this:

How many rides of each rate type were taken?

Taxis in New York City use a range of different rate types for different kinds

of trips. For example, trips to the airport are charged at a flat rate from any

location within the city. This section shows you how to construct a query that

shows you the nuber of trips taken for each different fare type. It also uses a

JOIN statement to present the data in a more informative way.

Finding the number of rides for each fare type

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken in the first week of January 2016, and return the total number of trips taken for each rate code:

The result of the query looks like this:

This output is correct, but it's not very easy to read, because you probably

don't know what the different rate codes mean. However, the rates table in the

dataset contains a human-readable description of each code. You can use a JOIN

statement in your query to connect the rides and rates tables, and present

information from both in your results.

Displaying the number of rides for each fare type

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, copy this query to select all rides taken in the first

week of January 2016, join the

ridesandratestables, and return the total number of trips taken for each rate code, with a description of the rate code:

The result of the query looks like this:

What kind of trips are going to and from airports

There are two primary airports in the dataset: John F. Kennedy airport, or JFK, is represented by rate code 2; Newark airport, or EWR, is represented by rate code 3.

Information about the trips that are going to and from the two airports is useful for city planning, as well as for organizations like the NYC Tourism Bureau.

This section shows you how to construct a query that returns trip information for trips going only to the new main airports.

Finding what kind of trips are going to and from airports

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken to and from JFK and Newark airports, in the first week of January 2016, and return the number of trips to that airport, the average trip duration, average trip cost, and average number of passengers:

The result of the query looks like this:

How many rides took place on New Year's Day 2016?

New York City is famous for the Ball Drop New Year's Eve celebration in Times Square. Thousands of people gather to bring in the New Year and then head out into the city: to their favorite bar, to gather with friends for a meal, or back home. This section shows you how to construct a query that returns the number of taxi trips taken on 1 January, 2016, in 30 minute intervals.

In Postgres, it's not particularly easy to segment the data by 30 minute time

intervals. To do this, you would need to use a TRUNC function to calculate the

quotient of the minute that a ride began in divided by 30, then truncate the

result to take the floor of that quotient. When you had that result, you could

multiply the truncated quotient by 30.

In your Tiger Cloud service, you can use the time_bucket function to segment

the data into time intervals instead.

Finding how many rides took place on New Year's Day 2016

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken on the first day of January 2016, and return a count of rides for each 30 minute interval:

The result of the query starts like this:

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/nyc-taxi-cab/compress-nyc/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

SELECT date_trunc('day', pickup_datetime) as day,

COUNT(*) FROM rides

WHERE pickup_datetime < '2016-01-08'

GROUP BY day

ORDER BY day;

Example 2 (sql):

day | count

---------------------+--------

2016-01-01 00:00:00 | 345037

2016-01-02 00:00:00 | 312831

2016-01-03 00:00:00 | 302878

2016-01-04 00:00:00 | 316171

2016-01-05 00:00:00 | 343251

2016-01-06 00:00:00 | 348516

2016-01-07 00:00:00 | 364894

Example 3 (sql):

SELECT date_trunc('day', pickup_datetime)

AS day, avg(fare_amount)

FROM rides

WHERE pickup_datetime < '2016-01-08'

GROUP BY day

ORDER BY day;

Example 4 (sql):

day | avg

---------------------+---------------------

2016-01-01 00:00:00 | 12.8569325028909943

2016-01-02 00:00:00 | 12.4344713599355563

2016-01-03 00:00:00 | 13.0615900461571986

2016-01-04 00:00:00 | 12.2072927308323660

2016-01-05 00:00:00 | 12.0018670885154013

2016-01-06 00:00:00 | 12.0002329017893009

2016-01-07 00:00:00 | 12.1234180337303436

Plot geospatial time-series data tutorial - set up dataset

URL: llms-txt#plot-geospatial-time-series-data-tutorial---set-up-dataset

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Optimize time-series data in hypertables

- Create standard Postgres tables for relational data

- Load trip data

- Connect Grafana to Tiger Cloud

This tutorial uses a dataset that contains historical data from the New York City Taxi and Limousine

Commission [NYC TLC][nyc-tlc], in a hypertable named rides. It also includes a separate

tables of payment types and rates, in a regular Postgres table named

payment_types, and rates.

To follow the steps on this page:

- Create a target [Tiger Cloud service][create-service] with the Real-time analytics capability.

You need [your connection details][connection-info]. This procedure also works for [self-hosted TimescaleDB][enable-timescaledb].

Optimize time-series data in hypertables

Time-series data represents how a system, process, or behavior changes over time. [Hypertables][hypertables-section] are Postgres tables that help you improve insert and query performance by automatically partitioning your data by time. Each hypertable is made up of child tables called chunks. Each chunk is assigned a range of time, and only contains data from that range.

Hypertables exist alongside regular Postgres tables. You interact with hypertables and regular Postgres tables in the same way. You use regular Postgres tables for relational data.

- Create a hypertable to store the taxi trip data

If you are self-hosting TimescaleDB v2.19.3 and below, create a [Postgres relational table][pg-create-table], then convert it using [create_hypertable][create_hypertable]. You then enable hypercore with a call to [ALTER TABLE][alter_table_hypercore].

Add another dimension to partition your hypertable more efficiently

Create an index to support efficient queries

Index by vendor, rate code, and passenger count:

Create standard Postgres tables for relational data

When you have other relational data that enhances your time-series data, you can

create standard Postgres tables just as you would normally. For this dataset,

there are two other tables of data, called payment_types and rates.

Add a relational table to store the payment types data

Add a relational table to store the rates data

You can confirm that the scripts were successful by running the \dt command in

the psql command line. You should see this:

When you have your database set up, you can load the taxi trip data into the

rides hypertable.

This is a large dataset, so it might take a long time, depending on your network connection.

- Download the dataset:

Use your file manager to decompress the downloaded dataset, and take a note of the path to the

nyc_data_rides.csvfile.At the psql prompt, copy the data from the

nyc_data_rides.csvfile into your hypertable. Make sure you point to the correct path, if it is not in your current working directory:

You can check that the data has been copied successfully with this command:

You should get five records that look like this:

Connect Grafana to Tiger Cloud

To visualize the results of your queries, enable Grafana to read the data in your service:

- Log in to Grafana

In your browser, log in to either:

- Self-hosted Grafana: at `http://localhost:3000/`. The default credentials are `admin`, `admin`.

- Grafana Cloud: use the URL and credentials you set when you created your account.

- Add your service as a data source

- Open

Connections>Data sources, then clickAdd new data source. - Select

PostgreSQLfrom the list. - Configure the connection:

Host URL,Database name,Username, andPassword

- Open

Configure using your [connection details][connection-info]. Host URL is in the format <host>:<port>.

- `TLS/SSL Mode`: select `require`.

- `PostgreSQL options`: enable `TimescaleDB`.

- Leave the default setting for all other fields.

- Click

Save & test.

Grafana checks that your details are set correctly.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/nyc-taxi-geospatial/index/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

CREATE TABLE "rides"(

vendor_id TEXT,

pickup_datetime TIMESTAMP WITHOUT TIME ZONE NOT NULL,

dropoff_datetime TIMESTAMP WITHOUT TIME ZONE NOT NULL,

passenger_count NUMERIC,

trip_distance NUMERIC,

pickup_longitude NUMERIC,

pickup_latitude NUMERIC,

rate_code INTEGER,

dropoff_longitude NUMERIC,

dropoff_latitude NUMERIC,

payment_type INTEGER,

fare_amount NUMERIC,

extra NUMERIC,

mta_tax NUMERIC,

tip_amount NUMERIC,

tolls_amount NUMERIC,

improvement_surcharge NUMERIC,

total_amount NUMERIC

) WITH (

tsdb.hypertable,

tsdb.partition_column='pickup_datetime',

tsdb.create_default_indexes=false

);

Example 2 (sql):

SELECT add_dimension('rides', by_hash('payment_type', 2));

Example 3 (sql):

CREATE INDEX ON rides (vendor_id, pickup_datetime DESC);

CREATE INDEX ON rides (rate_code, pickup_datetime DESC);

CREATE INDEX ON rides (passenger_count, pickup_datetime DESC);

Example 4 (sql):

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "payment_types"(

payment_type INTEGER,

description TEXT

);

INSERT INTO payment_types(payment_type, description) VALUES

(1, 'credit card'),

(2, 'cash'),

(3, 'no charge'),

(4, 'dispute'),

(5, 'unknown'),

(6, 'voided trip');

Energy consumption data tutorial

URL: llms-txt#energy-consumption-data-tutorial

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Steps in this tutorial

- About querying data with Timescale

When you are planning to switch to a rooftop solar system, it isn't easy, even with a specialist at hand. You need details of your power consumption, typical usage hours, distribution over a year, and other information. Collecting consumption data at the granularity of a few seconds and then getting insights on it is key - and this is what TimescaleDB is best at.

This tutorial uses energy consumption data from a typical household for over a year. You construct queries that look at how many watts were consumed, and when. Additionally, you can visualize the energy consumption data in Grafana.

Before you begin, make sure you have:

- Signed up for a [free Tiger Data account][cloud-install].

- [](#) [Signed up for a Grafana account][grafana-setup] to graph queries.

Steps in this tutorial

This tutorial covers:

- [Setting up your dataset][dataset-energy]: Set up and connect to a

Tiger Cloud service, and load data into the database using

psql. - [Querying your dataset][query-energy]: Analyze a dataset containing energy consumption data using Tiger Cloud and Postgres, and visualize the results in Grafana.

- [Bonus: Store data efficiently][compress-energy]: Learn how to store and query your energy consumption data more efficiently using compression feature of Timescale.

About querying data with Timescale

This tutorial uses sample energy consumption data to show you how to construct queries for time-series data. The analysis you do in this tutorial is similar to the kind of analysis households might use to do things like plan their solar installation, or optimize their energy use over time.

It starts by teaching you how to set up and connect to a Tiger Cloud service,

create tables, and load data into the tables using psql.

You then learn how to conduct analysis and monitoring on your dataset. It also walks you through the steps to visualize the results in Grafana.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/energy-data/compress-energy/ =====

Simulate an IoT sensor dataset

URL: llms-txt#simulate-an-iot-sensor-dataset

Contents:

- Prerequisites

- Simulate a dataset

- Run basic queries

The Internet of Things (IoT) describes a trend where computing capabilities are embedded into IoT devices. That is, physical objects, ranging from light bulbs to oil wells. Many IoT devices collect sensor data about their environment and generate time-series datasets with relational metadata.

It is often necessary to simulate IoT datasets. For example, when you are testing a new system. This tutorial shows how to simulate a basic dataset in your Tiger Cloud service, and then run simple queries on it.

To simulate a more advanced dataset, see [Time-series Benchmarking Suite (TSBS)][tsbs].

To follow the steps on this page:

- Create a target [Tiger Cloud service][create-service] with the Real-time analytics capability.

You need [your connection details][connection-info]. This procedure also works for [self-hosted TimescaleDB][enable-timescaledb].

Simulate a dataset

To simulate a dataset, run the following queries:

Create the

sensorstable:Create the

sensor_datahypertable

If you are self-hosting TimescaleDB v2.19.3 and below, create a [Postgres relational table][pg-create-table], then convert it using [create_hypertable][create_hypertable]. You then enable hypercore with a call to [ALTER TABLE][alter_table_hypercore].

Populate the

sensorstable:Verify that the sensors have been added correctly:

Generate and insert a dataset for all sensors:

Verify the simulated dataset:

After you simulate a dataset, you can run some basic queries on it. For example:

Average temperature and CPU by 30-minute windows:

Average and last temperature, average CPU by 30-minute windows:

Query the metadata:

You have now successfully simulated and run queries on an IoT dataset.

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/tutorials/cookbook/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

CREATE TABLE sensors(

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

type VARCHAR(50),

location VARCHAR(50)

);

Example 2 (sql):

CREATE TABLE sensor_data (

time TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL,

sensor_id INTEGER,

temperature DOUBLE PRECISION,

cpu DOUBLE PRECISION,

FOREIGN KEY (sensor_id) REFERENCES sensors (id)

) WITH (

tsdb.hypertable,

tsdb.partition_column='time'

);

Example 3 (sql):

INSERT INTO sensors (type, location) VALUES

('a','floor'),

('a', 'ceiling'),

('b','floor'),

('b', 'ceiling');

Example 4 (sql):

SELECT * FROM sensors;

Plot geospatial time-series data tutorial - query the data

URL: llms-txt#plot-geospatial-time-series-data-tutorial---query-the-data

Contents:

- Set up your dataset for PostGIS

- Setting up your dataset for PostGIS

- How many rides on New Year's Day 2016 originated from Times Square?

- Finding how many rides on New Year's Day 2016 originated from Times Square

- Which rides traveled more than 5 miles in Manhattan?

- Finding rides that traveled more than 5 miles in Manhattan

When you have your dataset loaded, you can start constructing some queries to discover what your data tells you. In this section, you learn how to combine the data in the NYC taxi dataset with geospatial data from [PostGIS][postgis], to answer these questions:

- How many rides on New Year's Day 2016 originated from Times Square?

- Which rides traveled more than 5 miles in Manhattan?.

Set up your dataset for PostGIS

To answer these geospatial questions, you need the ride count data from the NYC taxi dataset, but you also need some geospatial data to work out which trips originated where. TimescaleDB is compatible with all other Postgres extensions, so you can use the [PostGIS][postgis] extension to slice the data by time and location.

With the extension loaded, you alter your hypertable so it's ready for geospatial

queries. The rides table contains columns for pickup latitude and longitude,

but it needs to be converted into geometry coordinates so that it works well

with PostGIS.

Setting up your dataset for PostGIS

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

- At the psql prompt, add the PostGIS extension:

You can check that PostGIS is installed properly by checking that it appears

in the extension list when you run the `\dx` command.

Alter the hypertable to add geometry columns for ride pick up and drop off locations:

Convert the latitude and longitude points into geometry coordinates, so that they work well with PostGIS. This could take a while, as it needs to update all the data in both columns:

How many rides on New Year's Day 2016 originated from Times Square?

When you have your database set up for PostGIS data, you can construct a query to return the number of rides on New Year's Day that originated in Times Square, in 30-minute buckets.

Finding how many rides on New Year's Day 2016 originated from Times Square

Times Square is located at (40.7589,-73.9851).

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

At the psql prompt, use this query to select all rides taken in the first day of January 2016 that picked up within 400m of Times Square, and return a count of rides for each 30 minute interval:

The data you get back looks a bit like this:

Which rides traveled more than 5 miles in Manhattan?

This query is especially well suited to plot on a map. It looks at rides that were longer than 5 miles, within the city of Manhattan.

In this query, you want to return rides longer than 5 miles, but also include

the distance, so that you can visualize longer distances with different visual

treatments. The query also includes a WHERE clause to apply a geospatial

boundary, looking for trips within 2 km of Times Square. Finally, in the

GROUP BY clause, supply the trip_distance and location variables so that

Grafana can plot the data properly.

Finding rides that traveled more than 5 miles in Manhattan

- Connect to the Tiger Cloud service that contains the NYC taxi dataset.

At the psql prompt, use this query to find rides longer than 5 miles in Manhattan:

The data you get back looks a bit like this:

[](#) To visualize this in Grafana, create a new panel, and select the

Geomapvisualization. Select the NYC taxis dataset as your data source, and type the query from the previous step. In theFormat assection, selectTable. Your world map now shows a dot over New York, zoom in to see the visualization.[](#) To make this visualization more useful, change the way that the rides are displayed. In the options panel, under

Data layer, add a layer calledDistance traveledand select themarkersoption. In theColorsection, selectvalue. You can also adjust the symbol and size here.[](#) Select a color scheme so that different ride lengths are shown in different colors. In the options panel, under

Standard options, change theColor schemeto a usefulby valuerange. This example uses theBlue-Yellow-Red (by value)option.

<img

class="main-content__illustration"

src="https://assets.timescale.com/docs/images/grafana-postgis.webp"

width={1375} height={944}

alt="Visualizing taxi journeys by distance in Grafana"

/>

===== PAGE: https://docs.tigerdata.com/api/configuration/tiger-postgres/ =====

Examples:

Example 1 (sql):

CREATE EXTENSION postgis;

Example 2 (sql):

ALTER TABLE rides ADD COLUMN pickup_geom geometry(POINT,2163);

ALTER TABLE rides ADD COLUMN dropoff_geom geometry(POINT,2163);

Example 3 (sql):

UPDATE rides SET pickup_geom = ST_Transform(ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(pickup_longitude,pickup_latitude),4326),2163),

dropoff_geom = ST_Transform(ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(dropoff_longitude,dropoff_latitude),4326),2163);

Example 4 (sql):

SELECT time_bucket('30 minutes', pickup_datetime) AS thirty_min,

COUNT(*) AS near_times_sq

FROM rides

WHERE ST_Distance(pickup_geom, ST_Transform(ST_SetSRID(ST_MakePoint(-73.9851,40.7589),4326),2163)) < 400

AND pickup_datetime < '2016-01-01 14:00'

GROUP BY thirty_min

ORDER BY thirty_min;